Mechatronics is not only about the motor, but rather getting the most out of the motors you have. To do that you have to step back and look at the whole system. Medium and high volume products can deliver high performance motion control and value-added features at low direct material costs if the work has been done up front to get the mechanics right.

All of the fancy algorithms in the world won’t fix a poorly designed mechanism. For example, a given application may have requirements for a gear train to be quiet which would then affect the design of tooth profiles, overall gear ratio, material selection, manufacturing specifications, etc. Often Simplexity engineers are tasked with reviewing an existing gear train design that had unfortunately overlooked a critical factor.

Gear train design considerations include:

- Selection of overall gear ratio and motor size. These are chosen to deliver the output velocity and torque/force that the application requires. Considerations include:

- Motor size

- Motor type such as brush DC, brushless DC, and stepper

- Cost

- Speed and torque ratings

- Available current and voltage from the drive circuitry

- Space for power transmission elements

- Allowable position and velocity error specifications

Each consideration will set up limits on the overall system design. Cross-discipline communication and iteration is often necessary to simultaneously meet them all.

- Material and manufacturing process selection. Power level and power density should be considered when selecting gear materials and manufacturing methods. In order to account for the forces applied, specific material and manufacturing steps need to be selected to keep the stresses and pressures within acceptable limits. The plastic gearing used in a 3D print mechanism would not withstand the tooth loading needed in a personal transportation device. Moreover, a device that is required to be much smaller than established product may require an upgrade in material strength to deliver the same torque or force.

- Cost vs. Precision. Higher AGMA (American Gear Manufacturers Association) quality levels will drive part cost up and decrease the list of vendors who are capable of meeting the requirements. The tooling that will be used to produce the gear should be given consideration. Keeping gates (the location where the plastic flows into the gear cavity to fill the part) centered is the best option to maintain roundness of the finished gear.

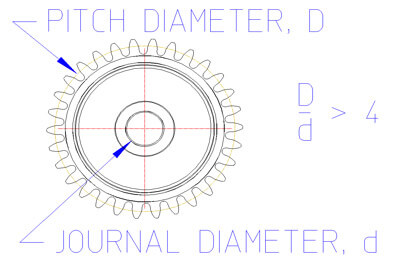

- Efficiency in the gear meshes and journals. Efficiency can be improved through increasing the pitch diameter to journal diameter ratio, using self-lubricating plastics and keeping speeds low.

- Gear Train Noise. Noise can be lowered by

- Keeping the contact ratio high enough that the load is shared across multiple teeth

- Keeping the motor speed (and hence the gear pitch line velocity) low

- Keeping low to moderate amounts of tip and root relief

- Using a belt and pulley for the first stage

- Using helical gearing is sometimes an option that works well

- Tooth Stress. Tooth Stress is computed based on the total loading on the gear. It rises with higher torque transmitted and falls with a larger face width or a greater number of teeth. Calculations for keeping tooth stress at acceptable levels due to fatigue with shock and velocity should also be performed.

- Requirements on backlash, especially due to effects of temperature and humidity. Plastic has a much higher thermal expansion than metals and many resins absorb moisture as well. Understanding the variations your gear train will experience due to temperature and humidity variations, both in shipping and during operation can influence the tooth form to be used.

BEYOND GEARS

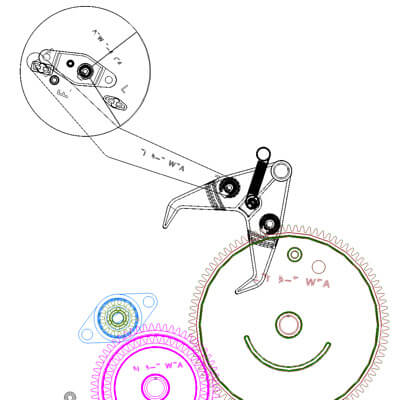

Unlike high-cost low-volume products, powertrain design for medium/high volume mechatronic devices often involves a tradeoff between the relatively lower cost of plastic and sheet metal parts versus the cost of additional motors, encoders, driver chips, board space and power. Getting more than one function out of a motor can extend the feature set of a product and minimize the direct material costs. An example is a printer transmission that shifts the paper feed power to run the pen service station when the pen carriage is parked at the end of its travel range. In this case two existing drives combine to provide a unique third function without adding another servo axis.

Mechanical elements can also enable unique product functions:

- One-way clutches free wheel in one direction allowing a single direction output from a bi-directional input or for an output to overrun its input.

- Torque limiting clutches are good as protection devices and deliver an accurate amount of torque to a load.

- Electric clutches can quickly couple or un-couple a load that needs to be driven part of the time.

- Geared swing arms are assemblies that are free to pivot through a range and can drive two different loads, depending on input drive direction. They can also serve as a direction rectifier for a single output.

- Latch mechanisms and linkages can generate complex spatial movements, dwells, and conditional behaviors.

- Viscous dampers are great for improving the quality of a device when sudden releases of energy occur, or a lightly loaded hinge needs to hold position.

- Cam mechanisms are often used when several actions must occur in a repeating, fixed sequence with respect to each other.

By combining these elements in creative ways it is possible to get the features necessary to improve performance, give market differentiation, or lower the cost to produce a mechatronic product.